Spotify never sold me my favourite artists' catalogue, it sold me access to it on their proprietary platform, in exchange for a subscription fee. So, I shouldn't be surprised to see that the money isn't going to the artists.

It's the season of Spotify Wrapped again, and my social feeds are filled with commentary about the streaming giant. Every year it seems like the share of posts critical of the meagre sums paid to artists grows by just a little bit. Meanwhile, the United Musicians and Allied Workers are lobbying the U.S Congress to force streaming platforms to adopt a more redistributive model.

From Ownership to Access

There was a time when music was something you owned. A vinyl collection was an archive, a statement, a physical manifestation of taste accumulated over years. CDs continued this logic — you bought an album, it was yours, you could lend it to a friend, sell it, or pass it down. The relationship between listener and music was one of possession.

The digital era shattered this. Music became an information good[1], infinitely reproducible at zero marginal cost. In the early 2000s, piracy was so rampant that when Apple introduced the iTunes Store in 2003, offering every song for 99¢, the industry celebrated its rescue. Inadvertently, however, this move cemented music's transformation into a commodity — discrete units to be purchased, downloaded, and theoretically owned (though DRM told a different story).

Then came streaming, and ownership vanished entirely.

The Platform as Landlord

In the streaming model, you don't own the music you listen to. You pay rent to the platform which hosts the files and grants you permission to stream them on-demand. Today music is no longer commodity, but content.

When you pay for Spotify, you're not paying for music. You're paying for the platform: the sleek UI, the recommendation algorithm, the playlists, the content delivery network infrastructure that beams songs and podcasts into your device. The music itself is merely the raw material — necessary but incidental, like the coffee beans in a café that's really selling the ambiance and the WiFi.

This is what Nick Srnicek calls platform capitalism[2]: the platform positions itself as an indispensable intermediary, extracting rent from every transaction while owning none of the underlying assets. Spotify doesn't make music. It doesn't employ musicians. It simply controls the access point and takes its cut.

The Attention Economy Swallows Everything

Imagine going back to 1995 and explaining to some post-punk kid that in twenty years, the vast majority of the world's music would be available on-demand in their pocket. Perhaps even they would celebrate this convenience as innovative and revolutionary.

But who asked for this? I certainly didn't.

On the platform, my music competes for the listener's attention against everything else — not just other artists, but podcasts, audiobooks, white noise playlists, and the infinite scroll of competing content. As Tim Wu argues, attention itself has become the scarce resource, and every platform is designed to harvest it[3]. Spotify isn't in the music business; it's in the attention business. Music is just the bait.

This transforms how music is made. The algorithm rewards certain patterns: short intros (skip rates matter), consistent output (the feed must be fed), playlist-friendly production (mood over vision). The artist becomes a content creator, optimising for engagement metrics rather than artistic statement. See also: On Attention.

The Musician as Platform Worker

So I decide to go against the grain — self-manage and self-distribute my music here. But even here, theoretically outside the platforms' grip, I am a platform worker[4].

What does this mean? It means I am responsible for my own means of production but dependent on platforms for distribution. It means I absorb all the risk while the platforms capture most of the value. It means my "independence" is largely illusory — I still need social media to promote, still need aggregators to reach streaming services, still need the algorithmic gods to smile upon me.

This is the condition Kurt Vandaele identified in gig workers across sectors: formal autonomy masking structural dependency[4:1]. The Uber driver owns their car but Uber controls the riders. The musician owns their masters but Spotify controls the listeners. Same logic, different content.

Cory Doctorow calls this trajectory enshittification[5]: platforms start by being good to users to attract them, then shift value to business customers, then finally extract all remaining value for themselves. Spotify's journey from "discover amazing music" to "here's an AI-generated playlist of background content" follows this arc precisely.

Is There Another Way?

Music is content and monetisation remains more-or-less an empty goal, replaced by the good vibes of doing something differently.

Bandcamp offered a glimpse of an alternative — a platform that actually prioritised artist revenue, waived fees on certain days, and maintained the logic of ownership (you buy, you download, it's yours). Then Epic Games bought it, laid off half the staff, and sold it to Songtradr[6]. The lesson: any platform that treats artists well is either unsustainable or will eventually be captured by those who don't.

Perhaps the answer isn't a better platform but fewer platforms. Direct patronage (Patreon, Substack), physical media resurgence (vinyl's comeback isn't just nostalgia), local scenes that exist outside the algorithmic gaze. Or perhaps we simply accept that recorded music has been irreversibly transformed, and pour our energy into the one thing that can't be streamed: live performance, presence, the unreproducible moment.

I don't have answers. But I think the first step is clarity about what we've lost — not just money, but the very relationship between music and listener. Access isn't ownership. Convenience isn't freedom. And content isn't art.

References

Witt, S., 2015. How Music Got Free: The End of an Industry, the Turn of the Century, and the Patient Zero of Piracy. Viking, New York. ↩︎

Srnicek, N., 2017. Platform Capitalism. Polity Press. ↩︎

Wu, T., 2016. The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads. Knopf. ↩︎

Vandaele, K., 2018. Will trade unions survive in the platform economy. Emerging patterns of platform workers' collective voice and representation in Europe, 33. ↩︎ ↩︎

Doctorow, C., 2023. "Enshittification." Pluralistic. https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/ ↩︎

Hogan, M., 2023. "Bandcamp's Union Has Been Laid Off." Pitchfork. ↩︎

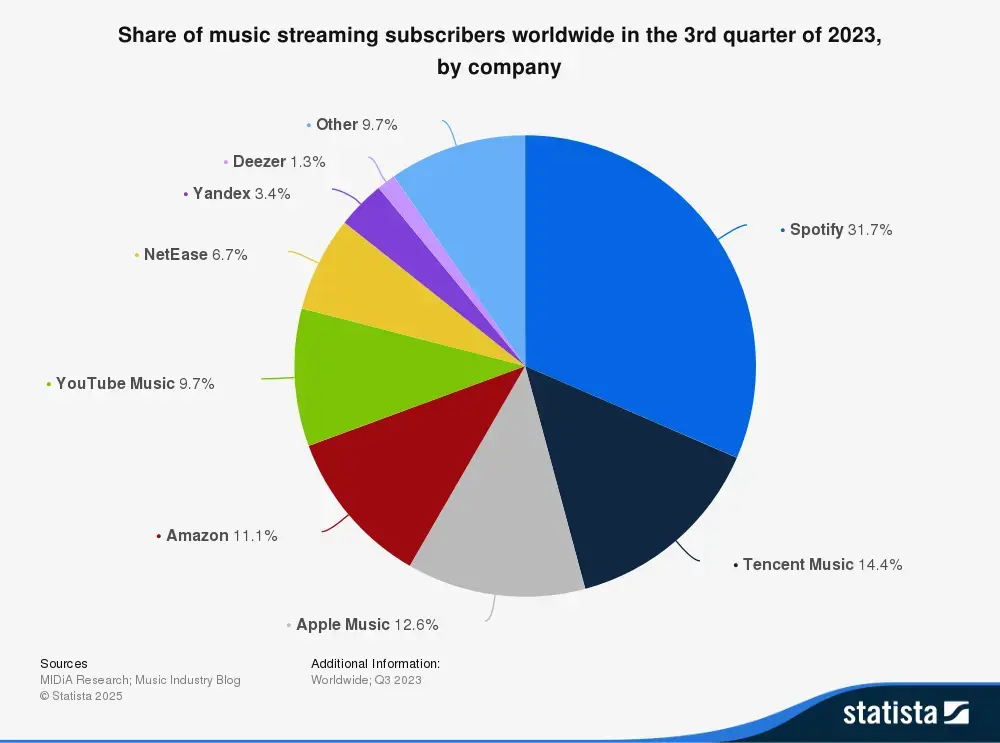

Music Industry Blog. (2024). Share of music streaming subscribers worldwide in Q3 2023, by company. Statista. Accessed: February 13, 2025. https://www.statista.com/statistics/653926/music-streaming-service-subscriber-share/ ↩︎